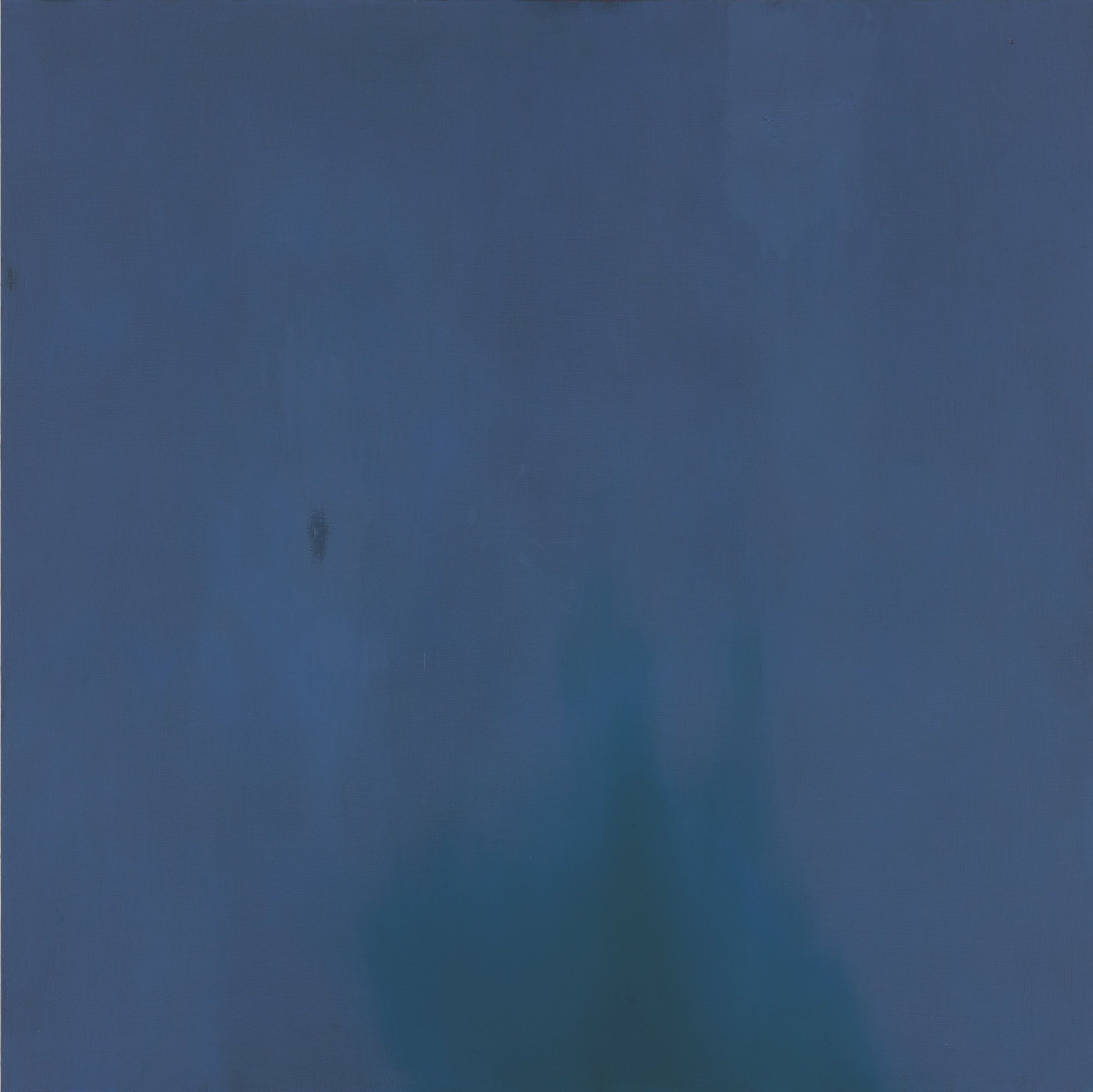

Painting 18:11 61x61cm oil on aluminium private collection UK

Painting 19:12 61x61cm oil on aluminium

Painting 19:11 61x61cm oil on aluminium private collection UK

Painting 19:14 61x61cm oil on aluminium

Painting 19:16 61x61cm oil on aluminium private collection Germany

Painting 18:10 61x61cm oil on aluminium private collection UK

Siemon Scamell-Katz, like all good artists, is the only kind of dreamer that counts, one with a fidelity to the world. Such dreamers let the world reveal and form itself around them, and they are capable of becoming enchanted with whatever appears. This is precisely the kind of fidelity that requires imagination—imagination that does not veer into fantasy but rather rises to the real, in service of discovering and receiving what’s appearing to the artist, often in ways that demand meaning and visual interpretation.

What appears in Scamell-Katz’s recent work is the marsh and the sea around the Norfolk coast where he chooses to live and paint, and he does for these worthy subjects what Brice Marden does for the Greek pebbles and stones that often inspire the latter’s paintings: transform them into a geography that is both other and human—a modernist terrain in which reality remains what it is while also undergoing the permutations of perception. One can’t simply look at a painting by Siemon Scamell-Katz; one is compelled to greet it, not in understanding but in gratitude, affection, delight, sometimes even terror—for there is something extra in his fields of modulated and muted greens and umbers and blues, something a little wild and inexplicable, touched with spirit. To greet a Scamell-Katz is to reply to and be in relation with felt reality, even as the work involves us in the unwrapping of perception; it is to engage in a proliferation of intimate, searching, imaginative responses in which everything—including sometimes a sense of self—is at stake. His paintings’ effects stop nowhere, but instead are continuous and indiscrete, placing one in a mood of pure attention to what we realize is other, is in excess of our perceiving. Reality, in this mode of reception, cannot be possessed or viewed in terms of usefulness, and if there is a moral aspect of Scamell-Katz’s work, it is to be found in this denial, which I view as particularly felicitous during a time when technology mediates our relations and understandings of reality, and too easily turns its various parts—whether the environment or people—into means.

By necessity a master craftsman, Siemon Scamell-Katz had to develop a means of painting that is equal to this kind of perception of reality—a means that puts his imagination at the disposal of the infinitely cascading relations at work in his experience of the marsh, say, or of the sea. No photograph or online image can come close to capturing what it’s like to be in the presence of a Scamell-Katz, for part of the pleasure, indeed part of the meaning of his work, lies in one’s appreciation of his technique, at least half of which is deployed on any of his painting’s worked surfaces. We take in a reproduction of his paintings at once, but in person we experience them in time—the complexity and authority of their craft demands this from us—permitting us to feel what it’s like to be immersed in and awake to reality’s incipience—what Henry James calls “the palpable present intimate that throbs responsive.” The great paradox of Scamell-Katz’s paintings is that they are easily situated within a modern, all-over, even minimalist abstract art tradition while at the same time seeming to embody the irreducible diversity of an actual landscape. In this very freedom that Scamell-Katz has won back from the familiar (including from familiar schools of painting), he has courageously submitted to the world as it is, but with an awareness of what Nietzsche calls the force of unvarying magnitude, of time’s and reality’s ferment and flow, of how much of it is wasted on us, and of our limited means of catching it.

Scamell-Katz does catch it, however. It’s there in the flickers and flashes beneath his brilliant surfaces, lending plastic credence to Wallace Stevens’ assertion that “we live in a constellation / of patches and of pitches.” Yet there’s nothing of the half-measure here: for all of his technical reliance on blending and muting and sheen, Scamell-Katz brooks no obfuscation or fuzziness in his work. He traffics less in the mysterious than he does in wonder. But wonder—wonder at all we can’t quite grasp—does not have to support a mystical emphasis on the ineffability of being. It needn’t lock up the mind, nor renounce the kind of response and responsibility that is demanded of us, in fact, by wonder itself. It’s as if this gifted and wise artist wants us to steer away from wonder which is merely a musing, and instead to see in his beautiful paintings what wonder really can be: a raw openness to the world we’ve inherited, and to our obligation to it.

Andrew Winer 2021